Lieutenant George E. Dixon

Arnold Becker

Corporal J.F. Carlsen

Frank Collins

C. Lumpkin

Miller

James A. Wicks

Joseph Ridgaway

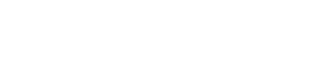

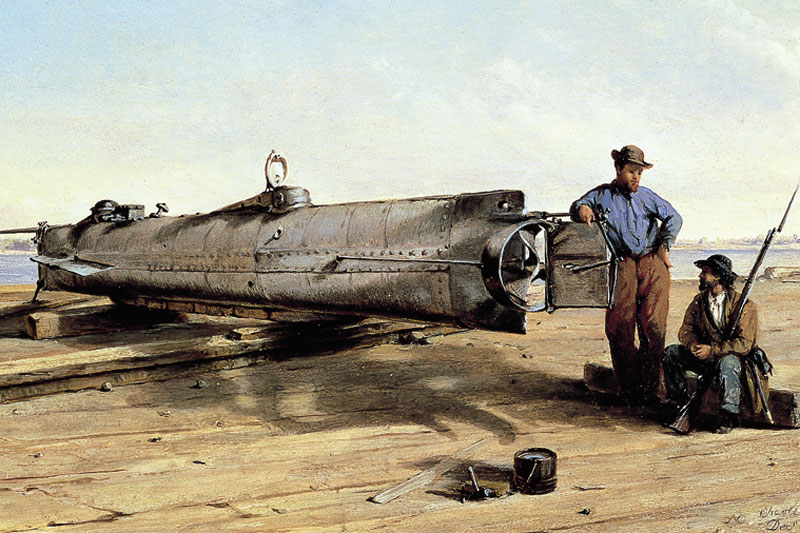

Two tragedies had now befallen the H. L. Hunley. The sinkings and visible recovery efforts that followed had created quite a stir in Charleston. It was not long before Rear Admiral John Dahlgren, the head of the Union blockading fleet, learned of the diving submarine from Confederate deserters. In response, Dahlgren ordered his blockading squadron to anchor in shallow water, hang ropes and chains over their sides as defensive measures, and deploy picket craft to keep torpedo-bearing boats away. These clever tactics were also the genesis of anti-submarine countermeasures.

Confederate General Beauregard was reluctant to put the Hunley back in service, writing: “It is more dangerous to those who use it than to the enemy.” Still, the submarine had persuasive backers including Lieutenants George Dixon and William Alexander, both of whom passionately believed she could be successful in breaking the blockade. Even they knew the Hunley had to be modified if she were to be successful. The Union’s anti-submarine moves coupled with the difficulty of controlling the Hunley’s depth and pitch while submerged led them to completely rethink the mode of attack.

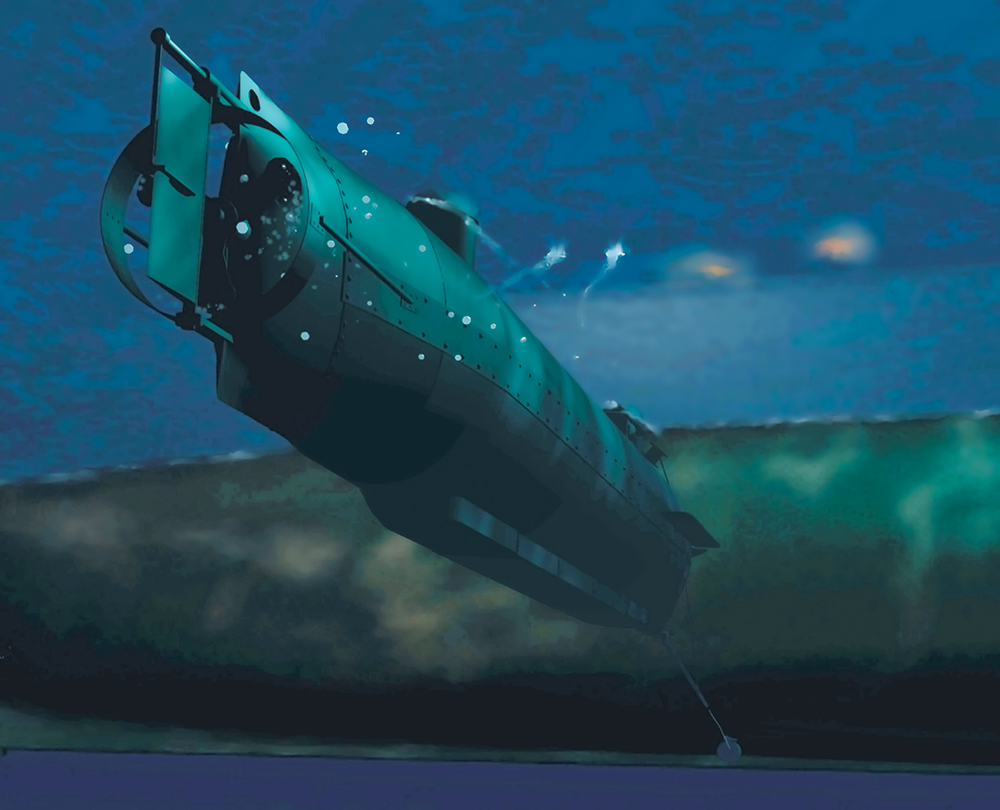

Towing an explosive device was abandoned for a more direct approach. A spar with a torpedo attached to its tip was mounted to the lower bow of the submarine. In this design, the plan was to ram the spar into the hull of an enemy ship, detonating the torpedo either on contact or by a trigger-pulled device. It was perhaps efficient, but, with a sixteen-foot spar, it left the crew dangerously close to the explosion.

There was little time, if any, to test the new attack strategy. Even though General Beauregard was reluctant, he finally agreed to let the Hunley try again, but only if the submarine did not dive and operated at the surface.

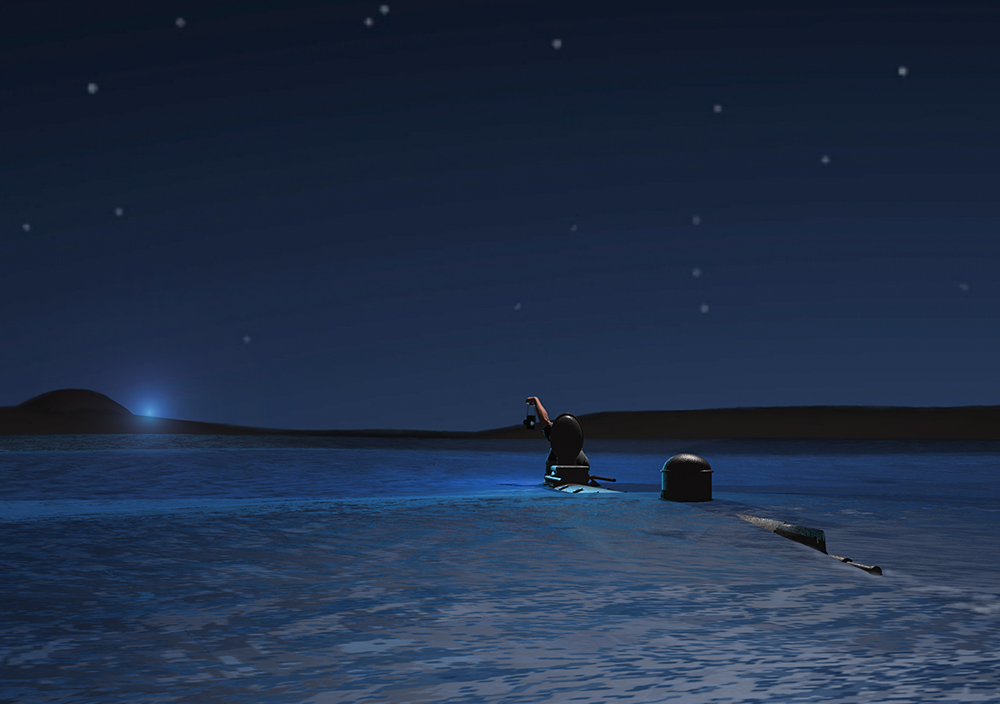

With the dangers of the submarine well-known, a new, courageous volunteer crew was selected and put under the command of Lieutenant Dixon. Soon the vessel would be ready to carry out its mission.